In September 2014, I left Microsoft to join a new product team at Amazon. The project itself is still classified, but it’s a v1 technology product, which means we’re starting from scratch. An exciting opportunity, but it changes the way one has to approach the role of user experience. Instead of researching existing products and wireframing, the conversations really need to focus on context of use, user habits, and information architecture.

Early on, it became clear that I’d be spending a lot of time sketching – too early for digital work, especially since digital work ends up being critiqued for typography, alignment, and color – not the nature of the core interactions.

And yet, I was a bit stuck. A big undefined problem space – and a big blank piece of paper. I did some mind mapping and some rudimentary interaction model proposals, but I was still daunted by the empty sheets. I experimented with a few of our core use cases, and realized they were perfect candidates for storyboarding.

My Storyboarding Criteria

When deciding whether a storyboard will be a useful tool, I apply these filters:

- The story should be focused on one or more users of the product, not the product.

- Never show more than 3 screens in one sequence – if you’re showing a long series of screens, you’re either jumping to solutions too fast or you’re ready for wireframing.

- The user’s context should usually change over the course of the story. If the user stays in one place the whole time, then you’re better off doing single environment sketches, not a storyboard.

- The storyboard should make the user’s objective clearer OR the storyboard should highlight existing interaction cliffs and pain points. (like switching from voice to controller on Xbox.

Storyboards don’t have to show happy paths – they can be valuable in depicting very common use cases and habits, but can also call stark attention to poor assumptions made in planning, or existing problems surfaced via research. On Windows Automotive, we relied on storyboarding heavily to ensure we were always thinking in the context of the vehicle. Many storyboards were simply marker on Post-Its, but the act of dividing the story into discrete beats often forced work on the transitions much earlier in the process, where they were much less risky.

Convinced that this form of storytelling was needed, I pulled out my sketchbooks with their nice paper, thinking perhaps the nice materials would jumpstart my mind. But my sketches were taking forever; I was getting too perfectionist on each frame. Thumbnailing wasn’t really conveying things the way I wanted, and no idea felt “special” enough to take up multiple sheets yet.

Then, I cut a sheet of paper in half. Specifically, a sheet of printer paper, letter size, sliced into two vertically oriented half sheets. And something unlocked.

It was an incredibly simple action, but it freed me up in many ways:

- Each panel was smaller and easier to shuffle, so I could reorder frames at will instead of doing an entire story on a single sheet

- The lengthwise aspect ratio was conducive to showing the user’s full body, in context.

- One idea per half-sheet allowed me to ink the captions directly, rather than scanning them in and digitally setting the captions later. Less steps = more story.

- With the paper cutters in the office supply rooms, it didn’t take much time to make the cuts I needed to replenish my supply.

- If you do need or want to trace, the printer paper is reasonably translucent (though susceptible to bleed, so having a plastic sleeve to protect the undersketch is handy)

Most importantly, I discovered: since each sheet now contained a single idea, it was easier to discard if I took an errant stroke. I finally decided to give up my sketching pencil and to ink directly onto each frame with Sharpies and graphic pens. There were a fair number of discarded frames, especially at first. Over time, I became more confident with my strokes (because the sheets were easily discarded) – and yet, if a stroke went awry, I was more likely to accept it and work with it, since I couldn’t erase or draw an alternate pencil line to reshape the drawing. I got faster, and I got better.

Elements of Story

While I sometimes joke about my work time spent coloring with markers, there is actually a great deal of influence, sublety and decision-making that goes into the choice of each frame, setting, and caption. Which views are you showing, and why? How has your user’s emotional state changed since the last frame? Their context?

In the first stage – thumbnailing and inking the images – I draw heavily on my improvisational experience, as it is largely the art of storytelling. There is a framework of shortcuts taken straight from our 100-level improv curriculum that can help guide you as you decide what to show.

It’s as simple as defining the CROW for your story. CROW stands for Character, Relationship, Objective, and Where.

- Character: Who is your user? What do they do?

- Relationship: What is your user’s relationship to other characters in the story, and to the device or software itself? What emotions go along with that relationship?

- Objective: What does your character WANT? This is where most storyboards go awry. I’ve seen so many storyboards that include frames like “Amy wants to browse the list, so she clicks the button. Let’s get one thing straight: humans never WANT to browse lists or click buttons. They want to find things and accomplish tasks. Focus on those motivations – the why, not the how. Storyboarding is so early in the process the how rarely matters- but if you don’t understand the why behind your users’ actions, you will fail.

- Where: What is the user’s context, and what is the location of your device or software? How does this change from frame to frame? Are there points in the story where your device/software isn’t present, and if so, where is the user then?

Without CROW, your storyboard may miss its mark, and often will focus too much on the implementation and not enough on the user context. Remember, this is human-computer interaction… and almost all of the other deliverables will focus on the computer. Keep this one focused on the human element as much as possible.

“Let’s get one thing straight: humans never WANT to browse lists or click buttons. They want to find things and accomplish tasks. Focus on those motivations – the why, not the how.”

Keeping it Simple

There were some lessons learned quickly. I started out inking the captions on directly before reviewing the storyboards with anyone, but found there were too many text-only corrections. So, I got correction tape (better than White-Out for thin paper like this, and cleaner) and I also began attaching the captions with a Post-It to start, reserving space for the caption to be inked later.

To save time, and to capitalize on the principles best described in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, I keep my users very generic in frame. A circle for the head, bold angular body not unlike a bathroom icon. No neck, hands like mittens, and just the slight curve of a butt to distinguish front and back from the side. This saves time, but it also changes how the boards are perceived. It allows me to keep the users gender neutral and prevents me from drawing unnecessary features which might interfere with the viewer’s ability to empathize. I’ll only add hair if I need to clearly distinguish front from back in subsequent frames, and I’ll only add facial features to indicate sleep or direction of gaze. The goal is to allow my viewer or reader to project themselves into the user’s shoes, which Scott McCloud will tell you becomes more difficult as a character becomes more fully rendered.

For complex environments or poses, steal shamelessly. A quick image search on Google will give you more than enough watermarked images to draw inspiration from. Print them to trace if you have to, or just do your best freehand attempt. The more you do, the better you’ll get. There are certain stock frames you’ll get very good at; like a hand holding a phone or a person sitting on a couch.

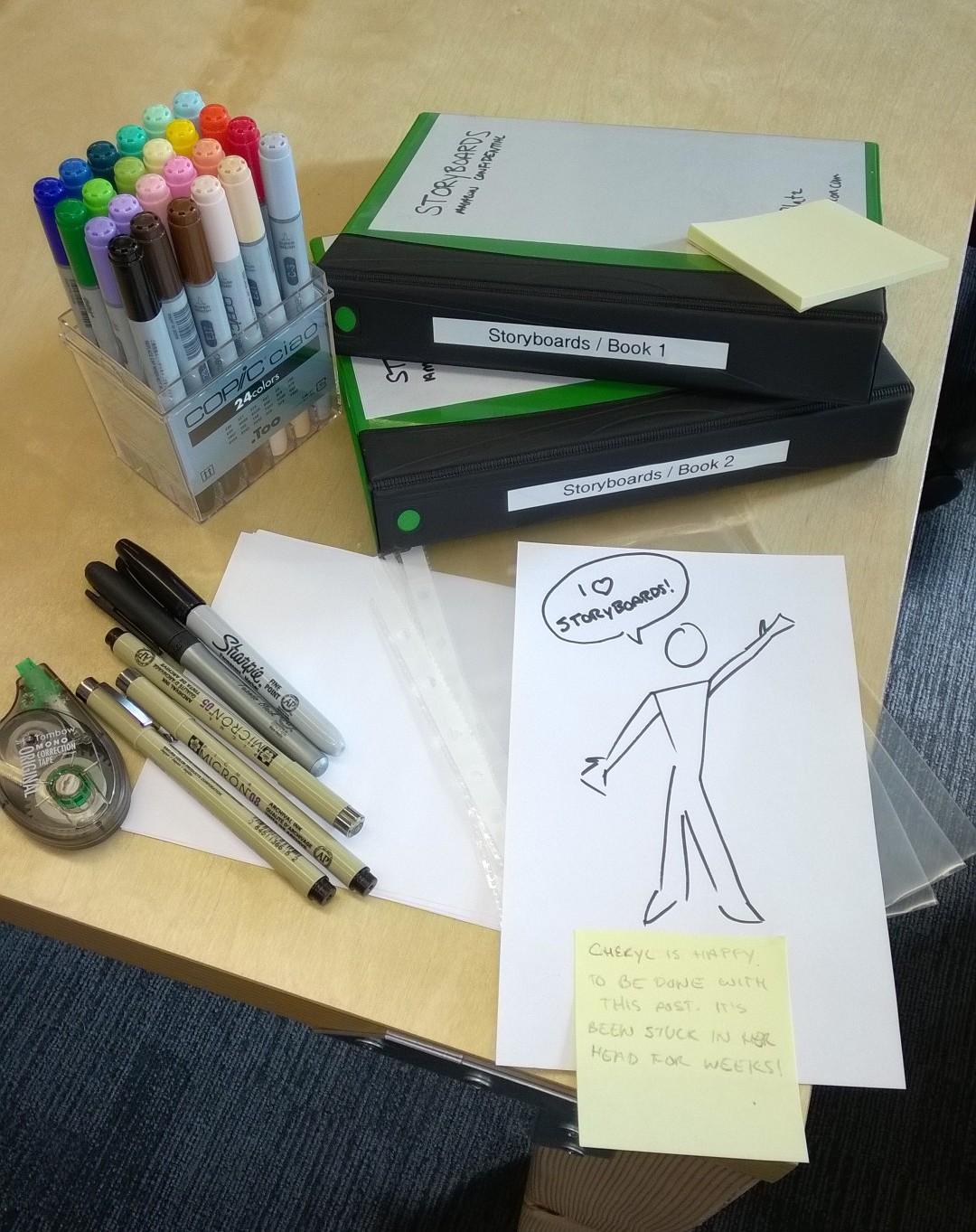

I also rediscovered very early on how important a little color is to the art of storytelling. In particular, when working with a single character or user, a change of clothing (as simple as a different shirt color) can indicate the passage of time in days or from evening to night. Color also directs the eye and adds depth, making the scene easier to picture. I did eventually decide to use crosshatching instead of solid black where it would occur, because the black tends to be overwhelming otherwise. (Pro tip: silly patterned pants are a great visual shorthand for pajamas.) I started out using colored pencils, but found them time consuming at this size, so switched to my Copic Ciao markers. Perhaps a bit overkill, but they’re fast and well-pigmented. Even though color is useful, don’t add it wantonly – figure out what the color is doing for you. Is it helping to indicate the same character in multiple frames? Is it calling attention to the focus of the frame? A status change? Sometimes I’ll do entire boards with just one or two punch colors and a grey to add some shadows where it helps break up an image. Each new color you add provides diminishing returns, so choose carefully.

Producing the Frames

My process for the more elaborate storyboards tends to be:

- Slice up some printer paper

- Use one sheet for some pencil thumbnails to settle on beats and environment layout

- Grab a Sharpie and ink the image for the first frame, leaving space for a caption

- Write the proposed caption on a Post-It and attach it to the B&W frame

- Repeat steps 3/4 as needed for each frame to complete the draft

- Review draft with product manager, make changes as needed

- Ink the captions

- Add color as needed

- Scan in finished panels

- Add panels to storyboard binders

Each frame ends up taking 10-15 minutes all told, more if it gets redone based on feedback. But early discssions on the B&W drafts can take hours at times, and will lead to many discarded frames and rearranged content. That’s normal, and that means your work is starting the right discussions.

The storyboards, once completed, are placed in 5.5″ x 8.5″ binders with individual sheet protectors. This way, I can easily remove the sheets and spread them out on a table to review without worrying about handling the fragile paper. If we have a large group, just review the scanned PDF. And the binders at that size fit in a larger purse or laptop bag easily – they can be toted across campus or into awkward spaces where projectors and monitors won’t work.

Socialization

It’s now been two solid months of storyboarding work (with other more production-focused UX work scattered along the way), which is wonderful in what it represents: a deep customer focus from the team and our decision-makers. When I started this journey, I intended for the storyboards to be an internal team tool. At this point, they’ve been shown to dozens of vice-presidents, and our CEO himself. They’re humble documents, but they jumpstart the right discussions. Because they’re humble, stakeholders feel empowered to provide feedback openly at the right level without getting drawn into details.

Meanwhile, the dev team used the storyboards as a north star to add context to deliverables. JIRA tasks and user stories were crafted based on single frames in the storyboards, and they were shown in context when discussing early implementation decisions prior to GUI availability.

Eventually, my design eye will shift back to prototypes and wireframes and comps. But this storyboarding phase, almost luxurious in its length, has been a wonderful immersion in what it means to be truly obsessed with a user’s context, objectives and desires. As we move deeper into the Internet of Things, this kind of storytelling will become more and more important. It’s not scalable to assume that customers will massively change existing habits just for the honor of using each new device. By truly examining the life and context of our users, we can find ways for the Internet of Things to insert itself seamlessly into existing habits, rather than continuously suggesting we add 15 more minutes each day for just 1 more device.

Next time you’re kicking off a project, grab a Sharpie, slice some printer paper, and see where it takes you. The worst that can happen is you start again on another half-sheet of paper. But you might just start an important journey into the ground truth your customer lives with every day.

Every great technology project should start with a compelling story.

Epilogue

I went on to expand on this concept in a bigger article on Medium, and then included it in my book Design Beyond Devices: Creating Multimodal, Cross-Device Experiences. I also teach storyboarding techniques in my multimodal design workshops.